「文学・文化研究者の訪日研究の意義」

クイーンズランド大学博士課程に所属するNF-JLEPフェローのローラ・クラクさんは、現在早稲田大学を拠点に、半年間の来日研究を行っています。自身の経験をふまえながら、「文学・文化研究者の訪日研究の意義」に関して、記事を寄稿してくれました。(日本語の記事の概要の後に、英語の原文が続きます。)

*****

記事の概要

日本に関する記事や映画作品の中で、日本は「変わった」また「風変わりな」国として描かれることが多い。日本のことをよく知らない人が勝手に言うのではなく、日本文学・文化を専門とする研究者も、日本を西洋と比較して、一歩引いた立場から、「異文化」として表現することが往々にしてある。その方が人々の興味をひくことは確かだが、この傾向について著者は警鐘を鳴らす。

そもそも著者自身も、出身国のオーストラリアとは違う日本の「異文化」をもっと知りたいと思ったからこそ、日本文学・文化を研究するに至った。

しかし研究者の一人となった今、作品の新たな解釈や印象を人々に与えてしまう可能性のある、責任ある立場から発信することに、真剣に向き合っている。文学・文化研究は、研究対象が抽象的であるという特性から、研究結果が単なる学者の創造物になってしまうかもしれない。自身の研究は日本を正しく描写できているか、結論付ける「日本」とは果たして存在するか、自問自答している。

答えを見つけるには、「本の世界」から飛び出して、日本で本物の文化を体験することが大切だ。著者は、現在東京に住みながら研究する機会を通して、自身の視点が「頭の中の」日本ではなく、「実際の」日本に向くことを感じている。

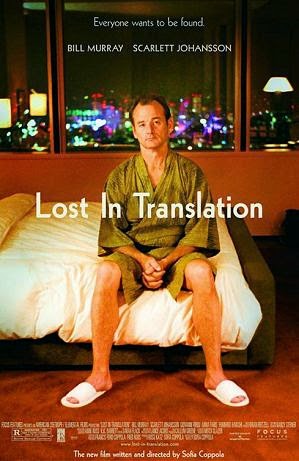

The Lost in Translation Problem: Intercultural engagement and the dangers of Othering

Previous publications in English can be found online in New Voices in Japanese Studies and the Electronic Journal in Contemporary Japanese Studies.

The depiction of Japan as an Othered cultural object has a long and difficult history, and is an issue that consistently comes to our attention. Whether it be for research purposes, intercultural engagement, popular cultural production, or even marketing for tourism, the construction and depiction of ‘Japan’ as a single consumable object is rife with dangers. In some cases, such as the semi-regular click-bait articles on ‘weird Japan’, this misrepresentation of Japan can be the product of a somewhat cynical push for casual reader engagement. In others, such as the alien-but-quaint-Tokyo of Sofia Coppola’s film Lost in Translation, this seems to come from a desire to embrace Japan and draw the main-stream film audience away from Western navel gazing. Of course, popular academia is by no-means disengaged from this issue, the ‘Unique Japan’ theme, bordering at times on Orientalist tones, runs the risk of perpetuating and encouraging research that homogenises and even disempowers the object it purports to represent.

It is worth noting that this Othering of which I speak is not only perpetuated by outsiders, but is a practice in which Japanese scholars also participate. This can be seen through the narrative of exceptionalism and self-Othering in the face of the ubiquitous ‘West’, as Sakai (1989, pg. 105) noted, Japan has the greatest sense of ‘self’ when it is acknowledged as Other against the ‘West’. Of course, this issue is by no means unique to Japan, and within the world of academia there are broad concerns about how best to deal with cross-cultural research. The delineated borders of acceptable representation and engagement are under constant discussion and critique. However, as part of the next generation of emergent Japan studies researchers I would like to lend another voice to the discussion.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should mention that I am part of Australia’s Pokemon and Sailor Moon generation of young people. My interest in Japanese culture and the language were sparked by, and find their ultimate roots in, my consumption of popular, translated, anime and manga. I subsequently graduated to classics such as Ghost in the Shell and Neon Genesis Evangelion and Baccano. My youthful understanding of ‘Japan’ was defined by worlds of hyper-real, big-eyed, vaguely European pasts and hyper-violent, fantastical futures. As such, my subsequent foray into Japanese literature and cultural studies was coupled with a desire to move beyond the simplicity of earlier impressions.

Depending on the interests of the academic concerned, the study of literature can serve many different masters, produce a cornucopia of interpretations and impressions, and have the power to change our understanding of the work or the world around it immensely. For cultural studies research, engagement with literature offers the opportunity to be deeply engaged with the realities of contemporary societies, cultural norms and power structures, and the role of creative works in both sustaining and challenging these. The role and purpose of literature within society is similarly up for debate and discussion: is the role of authors to sell books, or to hold up a painting to society, ala Dorian Gray? Or for another perspective, perhaps consider the words of Ōe Kenzaburo (1995, pg. 9):

I wish it my task as a novelist to enable both those who express themselves with words and their readers to recover from their own sufferings and the sufferings of their time, and to cure their souls of the wounds.

The risk with the study of cultural products, is one ultimately of abstraction. The lines between the creative work, the culture from which it comes, and the representations it contains, can become blurred. However, it is important for us to remember that creative works such as Kimi no na wa can no more be contemporary Japan, than Gossip Girl the United States of America, or for that matter, Lost in Translation Tokyo. Without critical, self-reflective approaches to research, the object that is ‘Japan’ can be become a creation of the thinker: interpreted through cultural products, reinforced by secondary literature, and supplemented with the inter-cultural philosophical generalisations. So, for my own research, the question then becomes, does the ‘Japan’ of which I speak even exist? How would I know?

There are no easy solutions or answers to these questions, but there are paths that can be taken, and one is to fight abstraction through interaction. An anthropologist does not write of a subcultural group with whom they had never interacted. So too, cultural studies cannot run the risk of locking itself away with its books and films. Although we have the potential luxury of taking a text and exploring the culture it represents from the privacy of our own offices, that does not mean that we should. ‘Japanese culture’ should not be spoken of as an abstracted object, generalised and simplified for the sake of fitting cultural theory. Instead, we need to encourage our early career researchers, to seize the opportunities available to them to engage, explore, and be curious beyond the words in the texts before them.

There are aspects of culture and society that cannot be fully recorded or communicated for consumption from afar, whether this be through the internal gaze or an external one. For my own research, the chance to engage with and explore the country that I purport to be interested in, pushes me to challenge my own assumptions, my own findings, and my unconscious commitment to constructs and theories that do not necessarily hold true to reality. With my own research, which is concerned with gender ideals, there is often a risk of reaffirming stereotypes. The simplest solution to this, however, seems to just be present in the culture I am trying to understand. Undertaking a daily life in Tokyo, as well as a research-life, creates opportunities and experiences beyond the confines of my books. It forces me to reorientate the ‘Japan’ in my head with the many different ‘Japans’ I see before me, pushing me to take responsibility for the individuals that my research seeks to represent.

References

Ōe, Kenzaburo, 1995. ‘Japan, the ambiguous, and myself: Nobel lecture”, World Literature Today, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 5-9.

Sakai, Naoki, 1989. ‘Modernity and its critique: The problem of universalism and particularism’ in M. Miyoshi and H. Harootunian (eds.), Postmodernism and Japan. Duke Univeristy Press. Durham. Pp. 93-122.